Boardroom coup with a devil-shaped paper trail.

Patch Notes (Faerûn Edition)

- Childhood DLC: sold off → devil-adjacent internship → came back with management experience.

- Parents: patched with tadpoles; now “supportive.” Disturbing, yes. Efficient, also yes.

- Deliverables: Steel Watch, city-wide mind Wi-Fi, polite threats on letterhead.

House style

- Politeness as blade; NDAs as love letters.

- Respects competence the way other people respect deities.

- Smiles like he’s already scheduled your downfall for Thursday.

The Dark Urge

Pop-up ads for murder. Close tab? Your call.

What matters

- Amnesiac origin: the knife came first, the conscience arrived later out of spite.

- Choices are the point: you can always speedrun character development while covered in evidence.

- Understands strategy. Accidentally collects people.

Workarounds

- Resist the urges: unlocks “conscience,” “camp awkwardness,” and “Withers is proud of you (probably).”

- Lean in: unlocks “drama,” “excellent cloak,” and “oops, a legacy.”

Astarion

Vampire spawn with 200 years of customer-service voice.

Known issues

- Work history: Cazador’s unpaid internship (eternal).

- Skillset: stealth, snark, knife literacy.

- Questline lets you break the cycle or ascend and become the HR memo.

Field notes

- Flirts like a lockpick: deft, slightly illegal, often successful.

- Sunlight and sincerity both require sunscreen.

Shadowheart

Cleric of Shar, memory on a timer, moonlight in the patch notes.

Known issues

- Shar by default; may drift Selûne if you demonstrate “basic kindness” and “not being a ghoul.”

- Axis: night, light, and the audacity of choice.

- Specialises in barbed honesty with a ribbon on it.

Field notes

- Talks like a locked door; opens like a library.

- Will save you, then critique your plan in the same breath.

Gale of Waterdeep

Ambition with pastry. Can become a god or make you dinner.

Settings

- Wizard extraordinaire; carrying a volatile Netherese artefact like it’s an accessory.

- Endgame ambitions include: ascend with the Crown, or choose you above godhood and live deliciously mortal.

- Mystra complications. Capital C. We are not taking questions at this time.

House style

- Flirts in footnotes, loves in paragraphs.

- Heroic options: bake, boom, or both.

Minthara

Lawful Hostile; treats conquest like brunch reservations.

Known issues

- Job title: Absolute commander; hobbies: war, vengeance, victory.

- Recruitable if you pass the interview (competence, conviction, small war).

Field notes

- Speaks in decrees; naps with a sword like it’s a pet.

- Finds your compassion confusing and, tragically, endearing.

Party Config: Vibe Check & Camp Duties

-

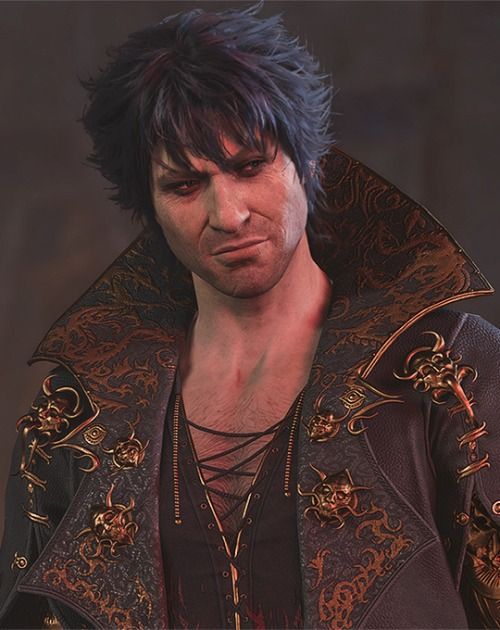

Gortash

Vibe: hostile LinkedIn.

Love language: signed alliances.

Critical fail on: whimsy. -

Dark Urge

Vibe: homicide, but make it sexy.

Love language: sharp objects.

Critical fail on: white carpets. -

Astarion

Vibe: flirty felony.

Love language: validation, jewellery, your blood in a cup.

Critical fail on: honesty and daylight. -

Shadowheart

Vibe: goth HR.

Love language: bandages and judgement.

Critical fail on: unlabelled relics. -

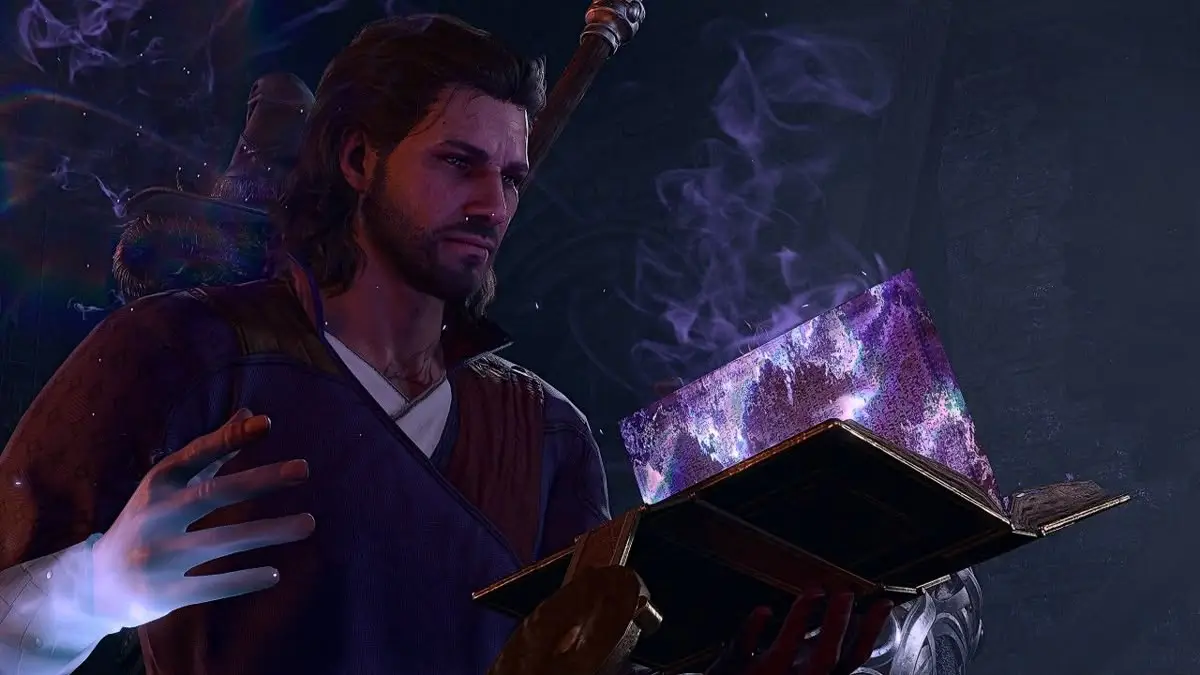

Gale

Vibe: dissertation with sparkles.

Love language: grand gestures and good soup.

Critical fail on: sussur bloom. -

Minthara

Vibe: conquest chic.

Love language: victory reports.

Critical fail on: small talk.